By Adekunbi Bello

“You will be delivering the keynote address,” she said. I attempted to object, but couldn’t muster the words when I opened my mouth. I was speechless and transfixed, and I felt goosebumps engulf me in their prickly embrace. This was my first public speaking engagement since the onset of COVID-19; I had gotten used to virtual sessions and webinars. I am super comfortable with the safety of my computer, sharing over the internet with audiences several thousand miles away. But this? I felt the news chip away at my confidence, especially since I had gained weight from comfort eating while battling depression and anxiety stemming from so much uncertainty and devastating news around the world, alongside the personal storms that I had to navigate in my corner of the universe. These thoughts were appeared within nano-seconds, and it took me a minute to find my voice. I finally replied, “It would be a pleasure.”

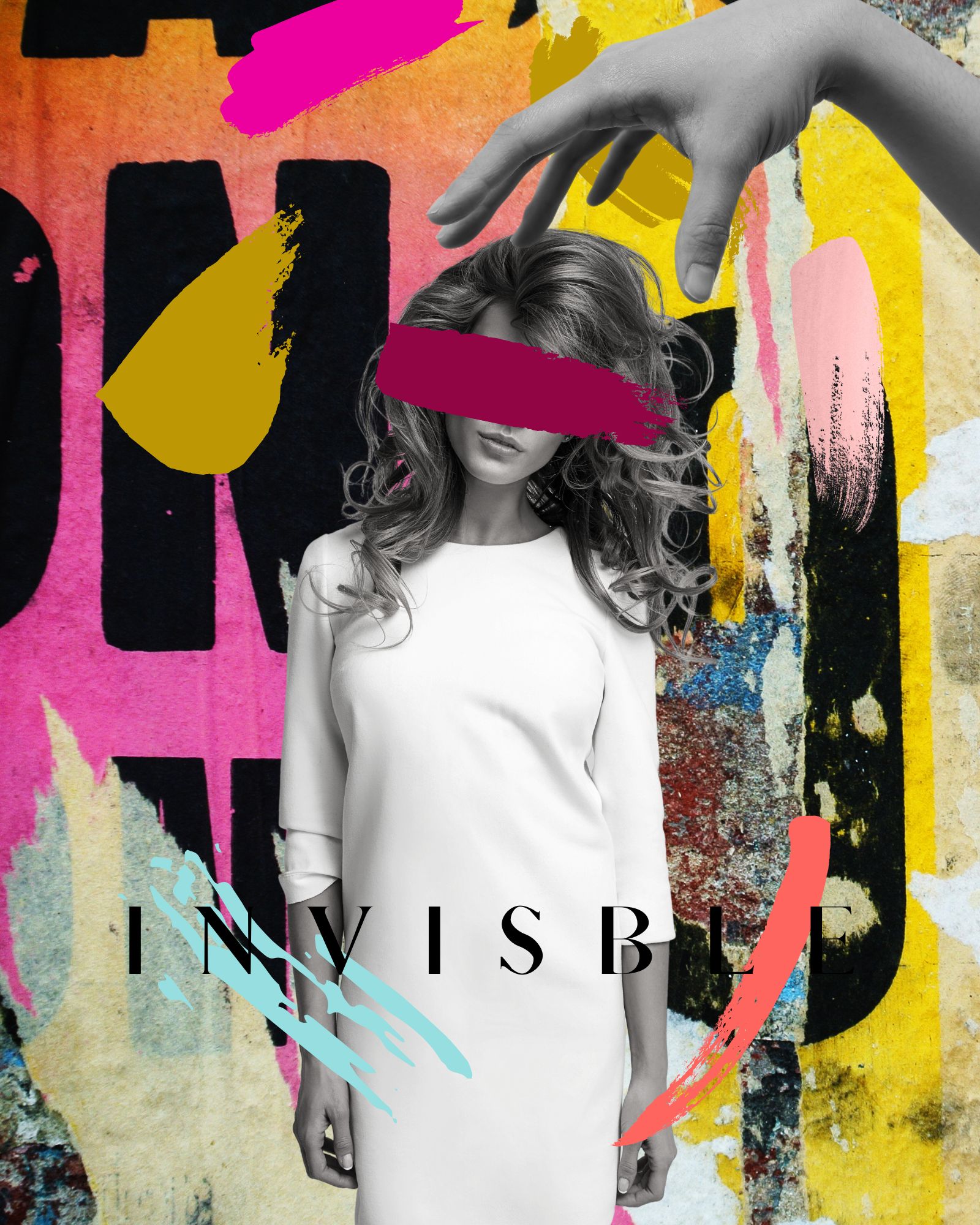

If failure is so familiar, why does the fear of it haunt us?

When the day came, the trepidation was merciless and unravelling. It felt like dipping into your favourite bag of chips, only that this time, it was over-salted. As the minutes went by, I thought about how to turn down the engagement and find my way out of the building. I sat in the speaker’s lounge, typing furiously on my phone instead of reviewing my presentation. I was petrified. All of my years of hard work, experience and expertise did not matter; all I saw was me not having anything to say and messing up my speech because I felt unqualified for such a task. I envisioned a stuttering woman, crippled with nervousness. I even had flashes of being booed off the stage. Yes, it was that bad!

Imposter syndrome is a pattern that causes individuals to doubt their abilities despite external evidence of their competence. It leads high-achieving people to believe that their successes are flukes rather than earned through ability (Psychology Today). Although it is not recognised as a psychological disorder, it is prevalent among highly accomplished and successful individuals.

The feeling of being a fraud and the fear of being exposed happens to the best of us. It is estimated, according to research, that about 70 per cent of women will struggle with imposter syndrome in their lives. This was apparently my moment.

Interestingly, a study also confirmed that men are 18 per cent less likely to experience self-doubt than women. The other male speakers looked at ease, calm, and collected when I looked around. They did not look like they had any sweaty palms or pre-engagement jitters. I wondered if they could perceive my fear and the severe rumbling in my stomach from the twists, turns, and knots forming on my insides just by the thoughts of the arduous task ahead of me. I felt disqualified and overwhelmed by self-doubt.

But I was not alone. Maya Angelou’s words kept me company.

“Each time I write a book, every time I face that yellow pad, the challenge is so great,” Angelou said. “I have written eleven books, but each time I think, ‘Uh oh, they’re going to find out now. I’ve run a game on everybody, and they’re going to find me out.’”

Indeed, I felt like I had run a game on everybody. Why was I even considered to be on this panel in the first place? I was too young to be here; I had just turned twenty-four last spring, and these other people were well-established professionals and known names well into their forties. “I should not be here,” I muttered. I needed this to be perfect.

I couldn’t afford to start on the wrong note, as my presentation would set a precedent for the whole event. I stared down at my dress. I wish I had worn a brighter colour, or maybe a higher heel. I tried to recoup and re-strategise as my coping mechanisms were failing by the second.

“But what is the worst that could happen?” my colleague and older friend said over the phone. I had desperately reached out to him to share my plight and ask for guidance to navigate the situation. I wanted a way out, but he had none of it. Instead, he jarred my memory and reminded me of how hard I had worked for a time like this, the experiences and lessons serving as preparation to bolster me to overcome such challenges. He called forth my expertise, reminded me of the several occasions where I had spoken to a multi-disciplinary crowd and gotten resounding applause, and how I got strangers to buy into my vision and see the world through my conviction.

“You’ve got this, Kunbi. Find a friendly face and speak to them.” That was it!

The relationship between our thoughts, emotions and behaviours: the cognitive triangle

The cognitive triangle illustrates how thoughts, emotions, and behaviour are interconnected. Our thoughts affect our emotions, which inform our actions, and the cycle repeats. Only interventions can disrupt this pattern.

Michelle Obama once spoke at a North London school during the UK leg of her book tour, where she shared her experience of feeling like an outsider throughout her life. “I had to overcome the question ‘am I good enough?” she said, discussing her experience at Princeton. “It’s dogged me for most of my life. Many women and young girls walk around with that question in their minds.”

More often than not, these thoughts of not being good enough, which could stem from a previous rejection or inherited shame, evoke feelings of fear or judgement, which fuels imposter syndrome.

These feelings spiral into actions such as a racing heart, tightness in the chest, muscle tension, and overwhelming fatigue, and (I will personally testify) nausea. When we question ourselves, we unknowingly send negative signals to our brains, resulting in us making terrible decisions or taking actions that we ordinarily wouldn’t consider. Hence, it was essential for me at that time to take charge of my thoughts, which, in turn, ultimately controlled my feelings and my behaviour.

Fortunately, I had picked up affirmations early on; they were my battle weapons for days when I felt insufficient. I donned my armour and stepped out on that stage, staring fear and failure in the face, embracing its familiar scent, and revelling in the breath of the worst results. Unsurprisingly, I made it.

A resounding ovation and positive reviews welcomed my words; one of the revered thought leaders in my field walked up to me and shared that he had quoted me in a post he just made on social media. I was elated! As he walked away, I felt the same old feeling creep in. I faltered and managed to hold my head high. I feared this fraud would now be found out again.

Nonetheless, if there was something I had learned, it was choosing to be kind to myself, even when I was my most prominent critic. It was a tussle of the fittest, as I was also my biggest fan. The fan won this time. I took in all the praise, basked in the overflow of positivity, and gave myself the grace to stay on it, living in that moment, taking up space, and finding my place right there at the top. Yet, I probably wouldn’t have done this if I had not placed that call with my friend.

Finally, we must be willing to be vulnerable. This is not a weakness but a strength. Opening ourselves up to be seen unashamedly for who we indeed are, being authentic and unapologetic. What is the worst that could happen? Do we fail? Embarrass ourselves? We fall? Well, then we pick ourselves up and try again! Failure will always be familiar. When Zig Ziglar shared that ‘F-E-A-R’ has two meanings, I felt that. “Forget Everything and Run’ or ‘Face Everything and Rise”. The choice is yours!

This is why we all need support on our journeys—a tribe committed to seeing us soar while anchoring our darkest days.

About Adekunbi

Adekunbi is a Visionary Fellow of the Vital Voices Visionary Program in Partnership with Estée Lauder Emerging Leaders Fund, a Global Youth Ambassador at Theirworld, an experienced public speaker and facilitator, and the Chief Operating Officer and co-founder of The Nutrition Network Africa. She works with a group of innovative women leveraging technology to revolutionise the management of chronic illnesses in Africa.